COVID-19 & Harm Reduction

The Health and Wellbeing of People who Use Drugs in the Midst of a Pandemic

Iowa recorded its first case of COVID-19 on March 8, 2020. Since this time, transmission of the virus has accelerated, and the pandemic moved quickly across the state. Like other national crises before it, COVID-19 has illuminated many existing health and social inequities. Yet not only does the pandemic highlight cracks within the healthcare system, the public health industrial complex, the criminal-legal enterprise, and the broader economy, it accelerates the growth of inequality and widens the existing social stratification.

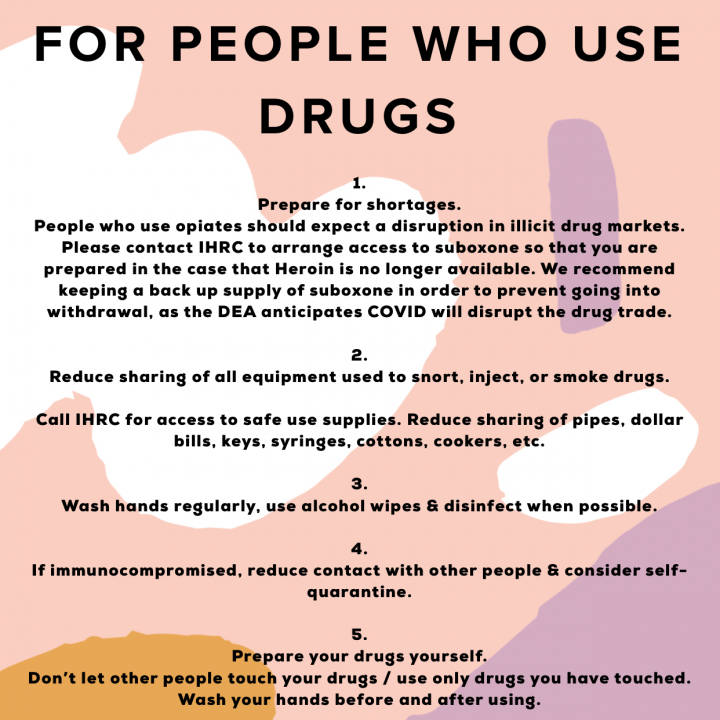

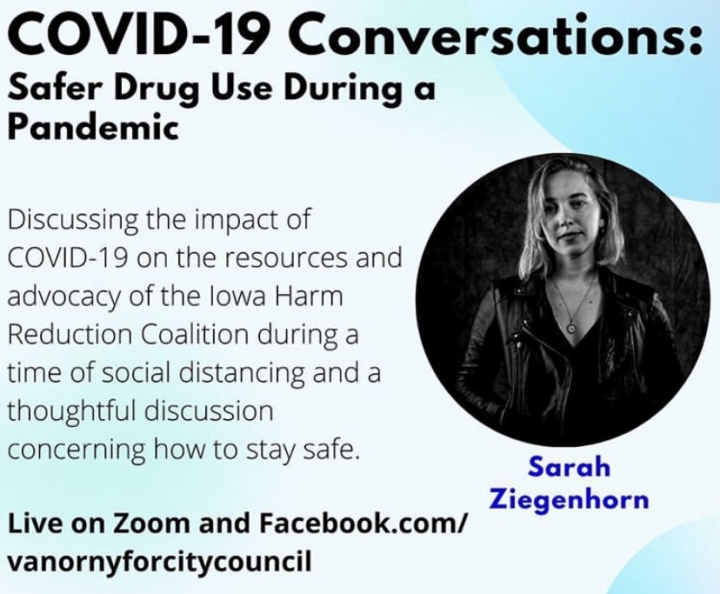

Since 2016, IHRC has advocated for the health, rights, and dignity of people who use drugs (PWUD) – as well as those whose lives are impacted by substance use and drug policy. It is possible to create parallels between the wellbeing of PWUD in our community and nearly any modern phenomenon. But for PWUD in Iowa, COVID-19 is not an exercise in theory or praxis. Since day one, people who use drugs have been deeply impacted by the pandemic. On a micro-level, PWUD are at significant risk for coronavirus transmission, as many members of this community are immuno-compromised; live in substandard conditions where social distancing is not possible; partake in substance use behaviors (eg. sharing pipes when smoking stimulants) that create exposure to respiratory droplets; and have other primary needs that distract and detract from their ability to implement a full set of COVID-19 prevention tactics. COVID-19 has transformed the way in which local law enforcement agencies engage with individuals who use, buy, or sell illicit substances. Criminal-legal systems have dramatically reduced prison and jail populations, in an attempt to mitigate the petri dish-like role that carceral settings tend to play in communities. The pandemic has fundamentally altered – for the better – the opportunities available to Iowans who are seeking treatment services for opioid use disorder. But it has also created social and economic upheaval, leading to shocks in the global illicit drug trade and resultant substitutions and shortages in Iowa’s drug supply. Individuals faced with social or physical isolation are experiencing emotional distress, disconnection, distress, and loneliness, which can catalyze a return to or dramatic increase in substance use. Isolated individuals who use opioids or heroin are faced with an increased risk of fatal overdose, due to a paucity of opportunities to be narcanned. And many struggle to access infectious disease and overdose prevention services, which has the effect of increasing the re-utilization and sharing of injection drug use equipment. Overall, the pandemic has engendered the conditions through which the existing, intertwined epidemics of HIV, hepatitis C, and overdose may experience new accelerations.

COVID-19 is an evolving phenomenon which has necessitated varying levels of engagement since March 2020. We have chosen to present IHRC’s COVID-19 related programming over time – rather than to organize this work according to theme – due to the ever-changing nature of the pandemic.

-

March 10, 2020

Preventing COVID-19 Transmission Among People Who Use Drugs: IHRC commits to providing essential services to people who use drugs over the course of the pandemic.

During the first two weeks of March, IHRC staff watched closely as organizations around the country began to make decisions reflecting the pandemic and the need to prevent transmission. For community-based Harm Reduction organizations, no matter how small or how under-resourced, one thing is for sure: Our services are critical to a particular subset of our community. During March 2020, it did not occur to us that we would close or suspend our direct service program. We simply made adjustments and took actions to ensure that our volunteers, staff, and clients could engage in services as safely as possible. Daniel Raymond, a long-time leader of the national Harm Reduction Coalition, participated in an episode of the podcast Narcotica in the early days of the COVID-19 response. His words were almost a call to action: for harm reduction service providers to mobilize quickly, to get out into the community and stay in touch with the people we care for and who care about us. Since early March, we have closed our program on two days due to employee illness, but are proud to have continued operating with no cases of illness reported among our client-base, volunteers, or staff.

Initially our office was quiet. The number of clients we served in March reached its lowest number ever. We made deliveries and connected with clients via the hotline, but the typical steady stream of individuals flowing in and out of our office was gone. And that was an okay thing – we shut down our drop in center and permitted just one client to enter our building at a time.

COVID-19 Goals, Pandemic Week 1: Staying Alive

Micro Goals:

- Enforce and adhere to guidance for hygiene, PPE, physical distancing, etc while providing direct services in order to keep staff, volunteers, and clients safe and healthy.

- Respond to client need while maintaining opportunities for precautions – eg. increase home deliveries.

- Maintain client services in order to prevent a spike in overdose deaths, HIV cases, HCV transmission, and bacterial infections.

- Provide clients with accurate, trustworthy information about COVID-19 so that they may take appropriate preventive measures.

- No COVID-19 cases among IHRC’s client, volunteer and staff community!!

DISTRIBUTE: COVID-19 resources for people who use drugs

CHERISH: Stimulant Use & Harm Reduction

CONCENTRATE ON: Rad Health Resources, Harm Reduction Participant Resources

CALL: Never Use Alone

BOOKMARK: Guidance for people who use drugs

BOOKMARK: Guidance for people who use drugs

SHARE: USU Coronavirus Comic

REFER: COVID-19 Safety Protocols

Vital Strategies: Resources for drug use and COVID-19 risk reduction

Harm Reduction Coalition: COVID-19 Resources

Harm Reduction Coalition: COVID-19 Resources for People Who Use Drugs and People Vulnerable to Structural Violence

Drug Policy Alliance: COVID-19 and Drug Policy

-

March 20, 2020

26 organizations from around Iowa urge state and local officials to take bold measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Iowa's jails and prisons.

87% of people in Iowa county jails are there currently because they cannot post bail

(Source: ACLU Iowa)

Jails (and prisons) are widely recognized by both medical and public health experts as ideal locations for viral infections to spread. For a virus like COVID-19, we could not create a more perfect environment for the bug to achieve its evolutionary goals: replicate inside the host and spread to as many new hosts as possible. Those who have been incarcerated in a jail or a prison, like many of the individuals we work with every day at the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition (a public health nonprofit that works to prevent infectious disease and overdose related to drug use), will tell you that there is little hope of maintaining a distance of six feet between inmates. Jails and prisons are crowded and human beings are living, eating, sleeping, breathing, and showering in very close proximity to one another. That’s why in New York City’s jails, the COVID-19 infection rate is 3.6% (as of Monday, March 30). This rate is almost double that seen four days prior.

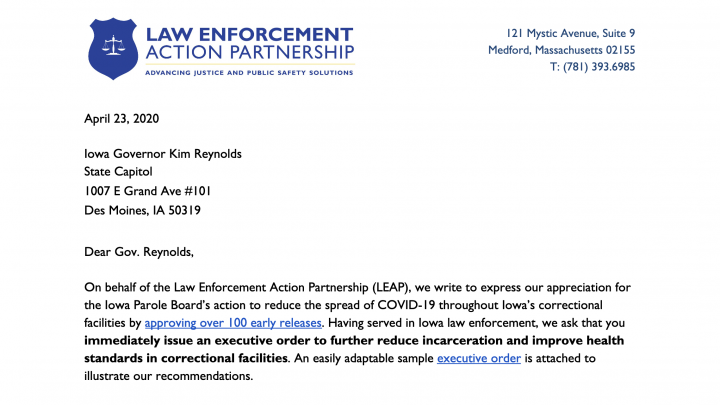

On March 20, a total of 26 Iowa advocacy organizations sent a letter to state and county officials recommending that they follow the advice of public health experts to make changes to Iowa’s criminal justice and legal systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. The letter urges officials “to partner with local public health experts in developing informed, immediately actionable steps to ensure that public safety and public health are as protected as possible.” This includes reducing jail populations by avoiding making new arrests in cases of low level, non-violent crimes, releasing people who are held merely because they cannot afford bail, and working to parole as many prisoners as possible.

Some of the highlights of the letter’s recommendations include:

-

- Limit the number of people being arrested. Issue citations and tickets rather than arrests.

- County attorneys and judges should use their discretion to limit the number of people put into jail, including reducing those held on pre-trial detention. They should also be especially mindful of inmates’ ability to post bail: 87 percent of the people in Iowa county jails are there because they don’t have enough money to post bail.

- County attorneys also should dismiss cases with minor offenses, such as drug possession.

- County jails should release people who would be released in the next 60 days anyway.

- Officials should limit the number of people who are detained or incarcerated for technical rule violations while on probation, such as testing positive for alcohol or drugs or missing a parole appointment.

- The governor should commute sentences for anyone whose sentence would end in one year anyway. She should commute the sentences for people whose sentences would end in two years who are especially vulnerable because of heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, or otherwise have a compromised immune system.

In addition to the ACLU of Iowa, organizations signing the letter are:

Iowa-Nebraska NAACP; Iowa Coalition Against Sexual Assault; Quad Cities Interfaith; Latinos Unidas para;; un Nuevo Amanecer; Iowa CURE; Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement; Project Iowa; St. Paul AME Church; League of Women Voters of Iowa; Inside Out Community Reentry Community; League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) of Iowa and LULAC national; NAMI Iowa; American; Friends Service Committee/Iowa Immigrants’ Rights Program; Des Moines Showing Up for Racial Justice; The Image Program; One Iowa; Rape Victim Advocacy Program; Interfaith Alliance of Iowa; Transformations Iowa; Iowa Coalition Against Domestic Violence; Transgender Voter Network; Regret No Opportunities; Just Voices Iowa; Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition

Mar 12 – The Incarcerated Population Is Especially Vulnerable to Coronavirus Filter Magazine

Mar 13 – Why Jails Are Key To ‘Flattening The Curve’ of Coronavirus TheAppeal.org

Mar 14 – Iowa Department of Corrections Cancels Visiting at All Prisons IDOC website

Mar 23 – CDC Releases guidance for all correctional facilities and civil/pretrial detention centers

Apr 15 – Thousands of masks produced for Iowa prisons after DOC sees first case of COVID-19 Des Moines Register

Apr 18 – Iowa Department of Corrections Director Beth Skinner asks county sheriff’s offices to stop transferring individuals who were ready to start their sentence in the state’s prisons. (citation des moines register, also found mentioned in this article)

Apr 22 – Iowa Department of Corrections begins conducting extensive testing at IMCC (Oakdale) (citation des moines register)

Apr 22 – Department expands COVID-19 Testing; 10 additional tests results are positive Iowa DOC press release

Apr 22 – Cases of COVID-19 in Iowa’s prison system triples; union leader issues warning Des Moines Register

May 1 – More COVID-19 cases reported in Iowa’s prison system Little Village Magazine

“The Iowa Medical and Classification Center in Coralville, better known as Oakdale Prison, was the first state prison to report cases of COVID-19. On April 10, IDOC disclosed a staff member at Oakdale had tested positive, and on April 19, Oakdale confirmed the first case among its inmates.”

May 2 – 20 Iowa Prison Inmates Have Now Tested Positive for COVID-19 WHOtv.com Des Moines

May 5 – Letters: Inmates deserve fair fight against virus Des Moines Register

May 12 – Jails and Prisons Must Reduce Their Populations Now TheAppeal.org

“This crisis is showing us that the unequal and brutal conditions of some communities threaten everyone, and we will not succeed in fighting the deadly and devastating impact of COVID-19 by ignoring our most vulnerable.”

May 12 – Iowa Department of Corrections Delays New Intakes As Coronavirus Continues To Spread In State Prisons IPR

“On April 18, IDOC Director Beth Skinner asked county sheriff’s offices to stop transferring individuals who were ready to start their sentence in the state’s prisons. … ‘We are starting to see more spread and have serious concerns regarding introducing inmates from counties into a COVID hotspot. Please know you can reach out to us on a case by case basis or if you are having issues with capacity or difficult individuals and we will evaluate each situation,’ Skinner wrote in an email to county sheriff’s offices on May 6.”

May 13 COVID-19 cases in Polk County Jail nearly twice the number previously reported, court record says Des Moines Register

May 13 In Iowa, COVID-19 is Not An “Equal Opportunity” Disease ACLU press release

May 14 6 staff, 47 inmates at the Polk County Jail now have COVID-19, officials confirm Des Moines Register

-

March 30, 2020

IHRC mobilizes community members to advocate for COVID-19 precautions in Iowa prisons and jails

In late March 2020, the epicenter of the global COVID-19 pandemic was a New York City jail. While New York may be one of the most crowded cities in the world, that isn’t necessarily why COVID-19 has emerged in its jails. Jails (and prisons) are widely recognized by both medical and public health experts as ideal locations for viral infections to spread. For a virus like COVID-19, we could not create a more perfect environment for the bug to achieve its evolutionary goals: replicate inside the host and spread to as many new hosts as possible. Those who have been incarcerated in a jail or a prison, like many of the individuals we work with every day at the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition (a public health nonprofit that works to prevent infectious disease and overdose related to drug use), will tell you that there is little hope of maintaining a distance of six feet between inmates. That’s why in New York City’s jails, the COVID-19 infection rate is 3.6% (as of Monday, March 30). Almost double the rate four days prior.

On March 20th, the Iowa Harm Reduction Coalition, along with 26 other organizations, signed onto a letter that called on Iowa’s Governor, Sheriffs, County Attorneys, and Department of Corrections Officials to take vital steps to prevent COVID-19 from incubating in Iowa’s jails and prisons. The letter recommends a number of other strategies that can be put in place to reduce the number of people who are incarcerated – a figure that currently sits at nearly 16,000 Iowans on any given day. We called upon our County Attorneys and Sheriffs to implement these recommendations as soon as possible.

The choice to ignore these recommendations will have unfortunate consequences on our entire community – not just the individuals who live on the inside of Iowa’s correctional system. The young woman arrested for possession of marijuana may transmit COVID-19 to her cellmate, or the officer who processes her upon arrival at the jail. From there, the virus can continue to spread exponentially within the jail and across the general community. Those working and living in Iowa’s prisons and jails must be afforded the same opportunities to practice social distancing as the rest of us. All of our lives depend on it.

Building on the momentum of the ACLU of Iowa’s leadership and the recommendations made by the coalition of 26 stakeholders, IHRC worked to leverage out networks and mobilize advocates to connect with county-level leadership. Our goal? To express the deep importance of COVID-19 prevention initiatives to the broader public, particularly when such initiatives are applied within the criminal justice system. During the final week of March, nearly 200 individuals participated in an e-mail based advocacy campaign, urging county sheriffs to implement the ACLU’s recommendations.

Flatten The Curve & Protect Incarcerated Iowans From Coronavirus

Tell your sheriffs and the state Attorney General that they need to take action now to stop COVID-19 and reduce the number of individuals currently incarcerated in Iowa prisons and jails!

COVID-19 Escalates in Prisons. Tell the CDC to Act Now!

Join us in calling on the CDC to include the release of people from prison and jails in its COVID-19 guidelines to slow the spread and save lives.

Take action to save lives during COVID-19

Demand that Governor Reynolds reduces incarceration and immigrant detention capacity, stops minor arrests, and ensures continued access to medication-assisted treatment (MAT)

Time is running out to prevent even more fatalities

Tell Congress to release people in prison at-risk of COVID-19

WATCH: Jail in the Age of COVID – A Webinar from LEAP, the Law Enforcement Action Partnership

MONITOR: The Coronavirus Response: Spotlight on State & Local Governments via The Appeal

ACT: The Justice Collaborative has compiled an excellent set of resources on COVID-19, including recommended actions for professionals working at every level of the criminal-legal system, steps for advocates, examples of successful campaigns from around the country, and key reports from public polling data.

EXPLORE: Information for county attorneys and public defenders from the Defender Services Office

READ: COVID-19 in Correctional and Detention Facilities — United States, February–April 2020

REVIEW: Guidance from the Vera Institute

WATCH: The Marshall Project covers how justice systems are responding to COVID-19 in each state

-

April 10, 2020

Sudden changes in federal laws improve treatment access for opioid use disorder

On March 31, SAMHSA and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) released guidance providing flexibility to prescribe buprenorphine to new and existing patients with opioid use disorder via telephone by otherwise authorized practitioners without requiring such practitioners to first conduct an examination of the patient in person or via telemedicine.

These changes are significant. Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT), which includes methadone, suboxone, and naltrexone, is tightly regulated by SAMHSA and the DEA and has historically been regulated through policies that are both restrictive and unique within medicine. One provision of this policy was to require MAT patients be seen in clinic in order to receive treatment and prescription refills. Advocates have long bristled at this policy, especially in states like Iowa, where the red tape surrounding physician licensing to prescribe buprenorphine means that few providers in Iowa treat MAT patients, and many patients must drive 2-4 hours one way to the nearest MAT provider. Advocates have seen telehealth as an ideal for the expansion of MAT services in rural states, noting that such a strategy will be key in mounting a significant response to the overdose crisis. In response to the global pandemic and the need to keep patients away from hospitals and as many people in their homes as possible, federal policy that prohibited the prescribing of suboxone in telehealth-based patient care was suddenly removed.

From the Urban Survivor’s Union: Nation’s Leading Drug Policy Experts Demand Medication Assisted Treatment & COVID-19 Reforms

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical to remember that we are still in the midst of an overdose crisis. While many regulators have argued that methadone and buprenorphine policies must be deliberately restrictive due to the risk of overdose, adverse medication effects, and medication diversion, the COVID-19 crisis has forced many regulating bodies to re-evaluate these policies in order to comply with the urgent need for communities to practice social distancing and sheltering-in-place. Multiple government agencies including SAMHSA, the DEA, Medicare, and Medicaid have recently announced policy changes to allow for more flexible prescribing and dispensing. While these changes are a step forward, clinics have been either reluctant or resistant to fully implement them to the extent allowable under law. In light of the evolving pandemic and the needs of the community, we must not allow fears of overmedication and diversion to outweigh the health risks caused by patients being forced daily to congregate in large groups, or being driven to an adulterated illicit drug supply.”

From the DEA: March 31st Letter Granting Telehealth Treatment

“In light of the nationwide public health emergency declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) on January 31, 2020, as a result of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is exercising its authorities to provide flexibility in the prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances to ensure necessary patient therapies remain accessible. As part of this effort, DEA has partnered with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to ensure authorized practitioners may admit and treat new patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) during the public health emergency. DEA has already announced that practitioners may prescribe controlled substances to patients using telemedicine without first conducting an in-person evaluation during this public health emergency under 21 U.S.C. 802(54)(D). Today, DEA notes that practitioners have further flexibility during the nationwide public health emergency to prescribe buprenorphine to new and existing patients with OUD via telephone by otherwise authorized practitioners without requiring such practitioners to first conduct an examination of the patient in person or via telemedicine.

BOOKMARK: COVID-19 Resources from the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts

SPEED READ: Stat Reviews the Sweeping Overhaul of MAT Services

REVIEW: SAMHSA’s guidelines for addiction medicine care during COVID-19

EXPLORE: American Psychiatric Association’s Telepsychiatry and COVID-19 resources and guidelines

STUDY: American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guidance for Substance Use Treatment & COVID-19

BOOKMARK: Vital Strategies Summarizes Key Resources on MAT and COVID-19

WATCH: Webinar from FORE: OUD and the Emergency Department Experience During COVID-19

WATCH: Webinar from FORE: MOUD within the Primary Care Safety Net During the COVID-19 Pandemic

EXPLORE: COVID-19 Resources from the Joint Commission

WATCH: Webinar series via Health Management on suboxone, telehealth, COVID-19, reimbursement, and more…

READ: The National Health Law Program – Overview on Using Medicaid to Respond to COVID-19

When individuals who receive their health insurance through state Medicaid programs are incarcerated in a jail, their care is no longer covered by Medicaid. The county or the entity that operates the jail becomes responsible for their care. This represents a 55 year restriction on the use of Medicaid for people in the correctional system. For patients with opioid use disorder and/or patients who are prescribed or in need of MAT, jails do not routinely continue their health care. Seeing these treatments as optional, criminal justice systems elect not to pay for these medications primarily as part of a cost savings measure. However, public health research has found that individuals leaving correctional facilities who have a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) are 36 times more likely to die of an overdose within the month following their release as compared to non-incarcerated individuals with OUD. Because of this, the CDC has recommended that correctional institutions – particularly jails – initiate or continue treatment with buprenorphine for individuals with a history of OUD and ensure that these patients are maintained on buprenorphine upon discharge.

Proposed COVID response legislation in the U.S. House of Representatives contains a provision that would allow inmates to be covered by state Medicaid benefits during periods of incarceration and immediately following incarceration. The purpose of this bill is to help jails and prisons offset the costs associated with COVID-19 treatments that they might otherwise be responsible for absorbing. However, it has significant added benefit for people who use drugs and would likely lead to a significant decrease in mortality among people leaving correctional institutions.

Section 30110 of the proposed legislation states: Allowance for medical assistance under Medicaid for inmates during the 30-day period preceding release. Provides Medicaid eligibility to incarcerated individuals 30 days prior to their release.

-

April 20, 2020

COVID-19 increases the vulnerability of Iowans who use drugs

On May 1, 2020 in Nature Medicine, Dr. Sarah Wakeman, a well respected Addiction Medicine Physician at Harvard University wrote in Nature Medicine, “Crisis leads to opportunity. COVID-19 presents unique and urgent challenges. However, it also presents an opportunity to create a healthcare system that truly addresses the needs of vulnerable populations, such as those with opioid use disorder. We must first act quickly to stave off a substantial increase in overdoses, an impending crisis on top of a crisis.”

Her message was clearly articulated in the piece’s title: “An overdose surge will compound the COVID-19 pandemic if urgent action is not taken”

She was reflecting in particular on the unique vulnerability faced by people who use drugs in light of COVID-19. She goes on to state:

“In the USA and around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived as the population was fighting a devastating opioid overdose epidemic. Urgent and decisive action is needed to protect particularly vulnerable populations, such as those with opioid use disorder, to prevent a compounding effect on public health.

As the global spread of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 continues, the pandemic’s impact on people who are already marginalized and vulnerable will be profound, and the ‘knock-on’ effect on public health will be severe. This is particularly true of people with opioid use disorder.

Those who are most vulnerable in our society are at greater risk of opioid addiction at the best of times. Under the preventive social distancing that is needed to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, but also exacerbates social isolation and despair, both of which are known risk factors for the development and exacerbation of addiction, they are at greater risk than ever. The odds are stacked against those living with opioid use disorder during this outbreak with heightened risks for infection with SARS-CoV-2 and also for overdose. In part because of many countries’ decision to criminalize drug use rather than offer treatment, rehabilitation, harm reduction and compassion, those who suffer from opioid addiction are also at greater risk of incarceration, homelessness and severe mental illness, predicaments that do not enable proper social-distancing measures and frequent hand washing. Co-occurrence of chronic medical conditions often predisposes these people to more-severe forms of COVID-191. Lack of economic opportunity also may predispose those needing to procure opioids to turn to illegal activities, further exacerbating an already difficult situation of rampant COVID-19 in US prisons.”

Exploring the Vulnerabilities Faced by People Who Use Drugs in the Midst of COVID-19

In addition to a potential increased risk of contracting the coronavirus, people who use drugs (PWUD) face a complicated network of risks and vulnerabilities brought on by the global pandemic. We break these down here.

Information Overload: Many IHRC clients report that COVID-19 is not a major priority in their life. “I just don’t care about it. I know that’s bad, but my life is already bad enough,” remarked one long-time IHRC participant. For people who struggle with survival on a day-to-day basis, the pandemic is “just another problem” to add to an ever growing list of worries. Combined with no internet access and a sense of mistrust of government that results from being criminalized for behaviors that they have been told are attributable to a medical condition (i.e. drug use), many believe COVID-19 to be a hoax.

Disruptions in Underground Economies: Some of the earliest warnings shared by drug user advocates in response to COVID-19 concerned the drug supply. In reports from Mexico and China in early March 2020, cartel leaders predicted major shortages to come in the U.S. stimulant and opioid supplies. Public health experts worried that such shortages may lead to increasing levels of drug substitution, creating a situation in which more powerful drugs contaminate the illicit drug supply and people buying drugs are unable to obtain information regarding the chemical composition of a bag sold as heroin or meth. Changes in the drug supply have been varied across the U.S., and Iowans have seen several fairly unique impacts. Over the course of March, April, and May 2020, methamphetamine is reported to be nearly impossible to obtain at times, and prices fluctuate wildly. Substitutions are common, with many people reporting that the bag of meth they purchased turned out to be table salt. Other changes are less benign, with people from across the state independently reporting concerns for Krokodile. Stimulant users from Knoxville, Burlington, Postville, Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, Waterloo, Dubuque, and more have noted an increase in psychosis and disorientation among meth users in their communities. Unknown alterations in the drug supply can cause significant adverse health outcomes.

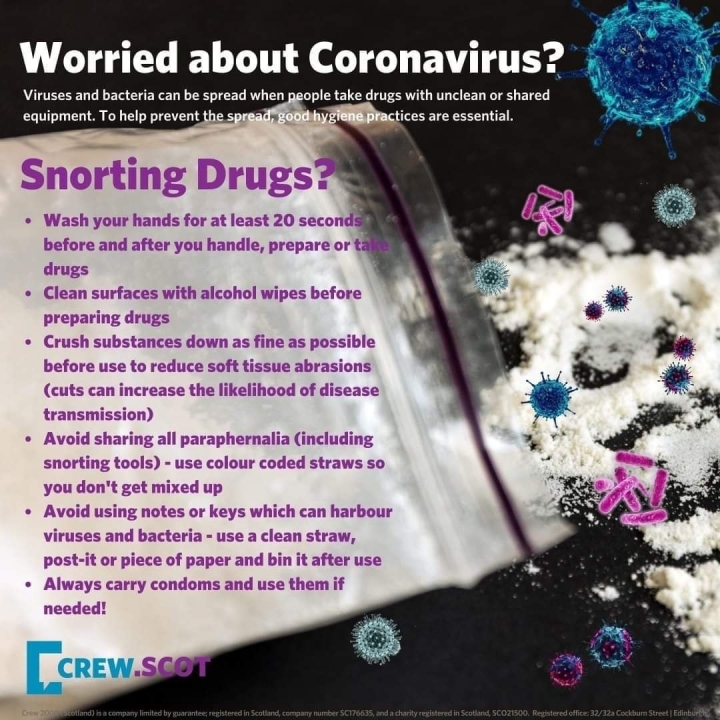

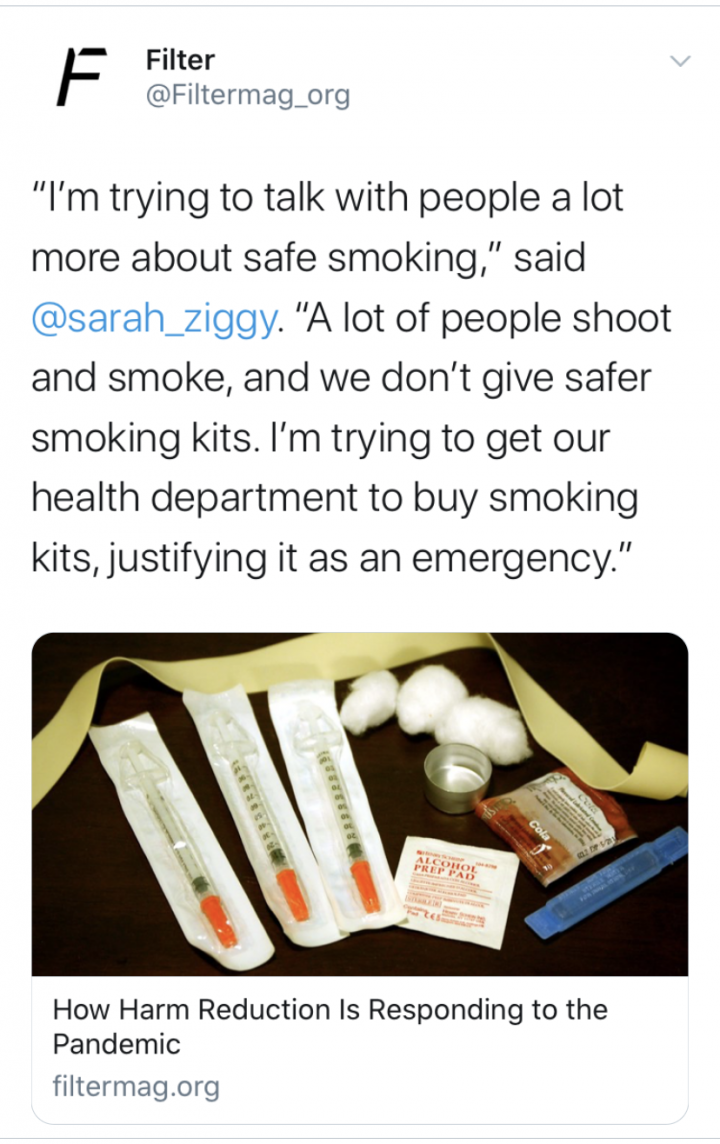

Smoking & Exposure to COVID-19: For people who use drugs, smoking stimulants like meth is a common practice in Iowa. But meth pipes often break, and groups of individuals typically share pipes within large groups in order to save funds. Because COVID-19 is transmitted through respiratory droplets, sharing pipes or smoking equipment is thus a means of exposure to the coronavirus. Many states have taken proactive measures to purchase safer smoking kits for clients experiencing substance use disorders. But Iowa is not one such state, and local law enforcement leaders have villainized these types of public health interventions in the past, using their seasoned expertise in virology and epidemiology to block uptake of this intervention.

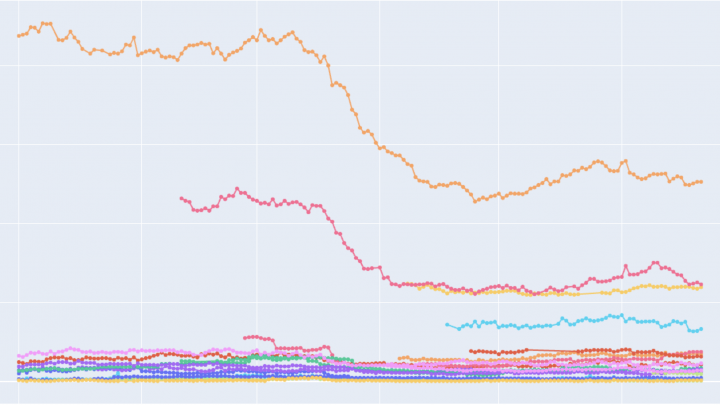

Syndemics – Resultant Increases in HIV/HCV: Many participants in IHRC’s program have assumed that harm reduction services are closed in the wake of the pandemic. IHRC logged some of the organization’s lowest numbers since opening in March and April (in terms of number of clients accessing services and number of infectious disease prevention materials distributed). This should raise concern among those who work to prevent and/or monitor HIV and HCV in the state – fewer individuals accessing prevention resources may mean that more individuals are re-using or sharing equipment used to snort or inject drugs. Experts around the country are ringing alarm bells as they witness similar data and observe that this may lead to new clusters of HIV and HCV.

Isolation and Despair – Increased Use and Overdose: A number of data points emerging from March, April, and May, 2020 indicate high levels of isolation and loneliness in the general population, along with high rates of consumption of legal psychoactive substances. Studies exploring the behaviors of people who use drugs during this period have also identified an increased frequency of use and increased quantities of use for both CNS stimulants and depressants. Some posit that the increases in rates of illicit substance use are a response to the massive changes occurring in the world. Widespread illness, tens of thousands of Americans dead, an economy in crisis, millions of people out of work, and a significant portion of the population with little to no financial reserves. Structural forces interact with one another in complex ways, influencing the human psyche and shaping our collective subconscious, creating the web through which pandemic modulates “diseases of despair,” and drug poisoning death. Drug researchers have long recognized that one’s emotional state can impact overdose risk – with fear, anxiety, sadness, trauma, isolation, and more, increasing one’s chances of a toxic response. At both the macro and micro levels, the stressors associated with the pandemic, and the desire to sooth, numb, or disappear them with drugs have created potential for a new wave of overdose deaths.

Social Distancing & Overdose: In order to survive an overdose, naloxone must be administered. Contrary to the belief of many, naloxone cannot be administered by a person who is experiencing an overdose – there is no window period for self administration. For individuals who use drugs and are spending more and more time alone due to the pandemic, this poses a significant dilemma: if they are to overdose, who will be there to administer naloxone? For this reason, epidemiologists predict an increase in overdose fatalities may be seen across the country as the pandemic is prolonged. Overdose deaths are oftentimes the product of a highly unpredictable drug supply + psychological stress + isolation and lack of opportunity for naloxone to be administered. The aforementioned conditions have a synergistic relationship, and they create the environment in which fatal overdose becomes probable. Prior to the pandemic, such intersecting conditions were certainly present but not pervasive. At the current moment, people who use drugs are experiencing a heightened risk of overdose due to a myriad of forces – but all of these risks can be resolved by the presence of naloxone and a person trained to administer it. As a result of large-scale social distancing, we may see the highest rates of drug overdose deaths to date in 2020.

Disruptions to Cash Flow: For some people who use drugs, the process of obtaining drugs on a daily basis is supported through work in informal and underground economies. Recycling cans and bottles; re-selling used goods; collecting cash donations on a street corner; and engaging in various forms of sex work are some of the ways in which people obtain the necessary funds to avoid experiencing painful opiate withdrawal symptoms. But shelter in place orders, the closing of businesses, the need to maintain 6’ from others, and additional features of the COVID-19 response have brought a halt to these informal kinds of labor. For those drug users who are very low-income and/or homeless, the disappearance of these income sources can be devastating and result in a situation where individuals must face potentially dangerous withdrawal syndromes or take on new and greater levels of risk to secure funds.

The Disappearance of Public Space: For many people who are experiencing homelessness, addiction, and/or extreme poverty, public facilities like parks, libraries, transportation hubs, community centers, and more provide respite during the day-time hours. Among participants in IHRC’s Cedar Rapids program, many individuals spend their days moving back and forth from public buildings to social service offices or community-based organizations. During the spring of 2020, many individuals lamented the sudden lack of spaces where they could feel safe, rest, or simply exist. The closure of these aforementioned facilities and offices has meant that for many individuals who live below the poverty line and struggle to stay housed and employed, much more of life is spent outdoors or on the streets.

Sheltering in Unsafe Places: On any given day, the majority of individuals incarcerated in a county jail, sleeping in a homeless shelter, or crowded together in an abandoned building have a substance use disorder. PWUD may cycle back and forth from one of these spaces to another, spending time in the local jail, moving into the shelter upon release, and eventually leaving the shelter for a 3-bedroom home housing 20+ transient residents. Each of these environments poses significant risk for COVID-19 exposure, as each offers little opportunity for adequate physical distancing. In the public health field, shelters, jails, and crowded low-income housing are widely recognized as the spaces in which communicable diseases, like COVID-19 flourish and become deeply entrenched. PWUD are, in general, likely to be immunocompromised due to unknown HIV status, malnutrition, or chronic opiate use. Systems designed to criminalize drug users, rather than provide support, care, or new possibilities, contain and shuffle people who use drugs within and between these high-risk spaces.

Filter is the online home for leading journalists and writers who cover the world of drug policy, addiction, harm reduction, drugs, treatment, and public health. Filter’s coverage of COVID-19 has centered critical conversations and issues that are otherwise absent from media representations of the pandemic and people who use drugs.

Drug-User Groups Innovate to Reduce the Risks of Using While Isolated

Even Jails are Decarcerating More than State Prisons

Tensions Rise in Kensington, Philadelphia, as Lockdown Bites

The Coronavirus Information Gap for Marginalized People

How the Pandemic is Restricting Health Options for People who Use Drugs

-

April 30, 2020

IHRC WEBINAR: Criminal Justice, Public Safety, & COVID-19 in Iowa.

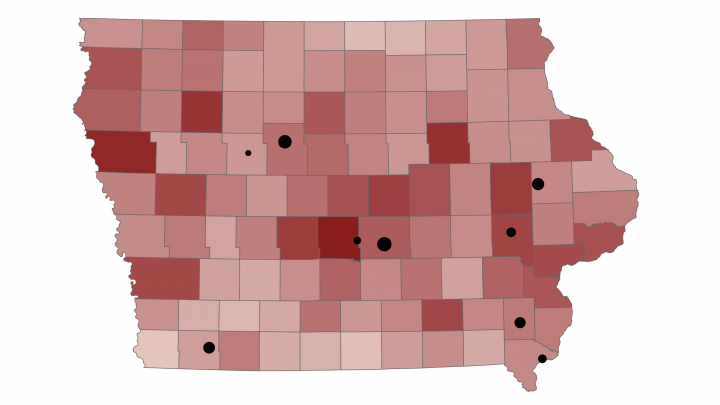

Jails and prisons have long been identified as community spaces that are at increased risk for infectious disease transmission. Physical (and social) distancing are oftentimes impossible in carceral settings, and people in these settings exist in close proximity to one another. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought heightened attention to the living conditions in jails and prisons. While COVID-19 cases are not expected to peak in Iowa until early to mid May, carceral institutions in other states have become the pandemic’s epicenter. New York City’s jails have the highest COVID-19 infection rates in the world, with 9.1% of Rikers Island residents testing positive as of April 20, 2020. Since early March, many Iowa counties have taken significant steps to reduce jail crowding and promote social distancing within court houses. On April 18 the first resident of Iowa’s prison system tested positive for COVID-19, leading Governor Kim Reynolds’ office to implement a series of new preventive measures for Iowa prison facilities. Strategies implemented at the state and local levels seek to prevent outbreaks from occurring in Iowa’s county facilities and reduce the number of law enforcement personnel, jail staff, incarcerated individuals, and criminal justice system professionals from contracting the virus and then spreading it into the community. But with Iowa’s projected COVID-19 peak still weeks away, some public health and health care professionals remain concerned regarding the preparedness of Iowa’s jails and prisons to adequately address the pandemic. This speculation is due in part to wide variation across Iowa’s 99 counties in measures implemented to prevent COVID-19 transmission in criminal justice settings. Despite few cases documented in IA prisons, some public health officials suggest that more action from the Governor’s office is needed to prevent the spread of the pandemic in state facilities.

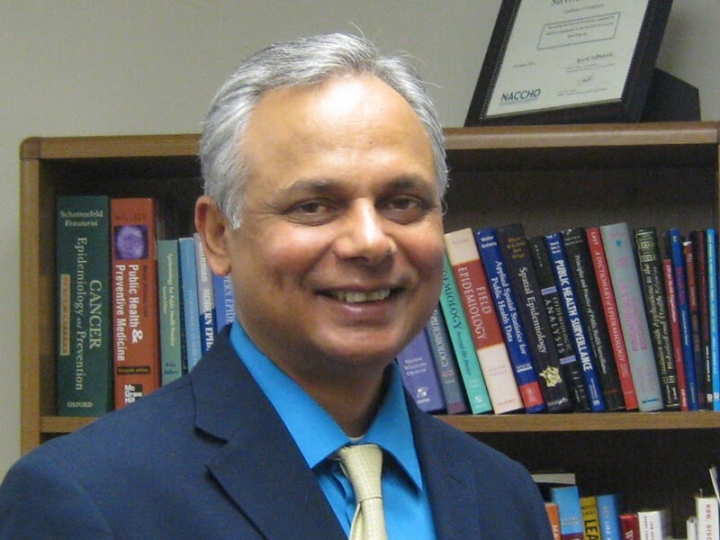

Nicole Linker,

Resident, Iowa Women’s Correctional Institution

Michelle Heinz,

Executive Director, Inside Out Reentry Community

Danny Homan,

President, AFSCME Iowa

Pramod Dwivedi,

Director, Linn County Public Health

Det. Sgt. Brad Kunkel,

Johnson County Sheriff’s Office

Captain Nate Neff,

Jail Administrator, Black Hawk County

Adam Sullivan,

Journalist, Cedar Rapids Gazette

Dr. Christopher Buresh,

Emergency Medicine Physician, University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics

Brian Leininger,

Attorney, LEAP (Law Enforcement Action Partnership)

Daniel Zeno,

Director of Policy & Advocacy, ACLU of Iowa

Ethan Rogers, Research Associate, Public Policy Center, University of Iowa

Mark Berg, Professor of Sociology, University of Iowa

-

May 10, 2020

Pandemic highlights the critical need for legal syringe access programs in Iowa

As COVID-19 first hit states around the U.S., Governors and Public Health administrators responded with statements that made clear that syringe service programs (SSPs) are a critical component of public health infrastructure, and that this crisis will be framed as an opportunity for the repeal of some of the more archaic and non-science based components of syringe access policy.

| Action Taken | Iowa | Neighboring States |

|---|---|---|

| Syringe service programs are legal to operate; syringes are viewed as public health tools, not paraphernalia or evidence of criminal behavior | ||

| Syringe exchange program workers declared essential personnel during COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Distribution of safer smoking kits is prioritized to prevent COVID-19 | ||

| Emergency funding is made available to sustain syringe exchange programs and support unique client needs during this time |

In Maine, the American Medical Association pressured the Governor to issue an Executive Order that would repeal the state’s 1-for-1 policy, a vestige of the early days of syringe exchange programming in the U.S., where individuals could only receive one syringe if they were willing to turn in an equal number of used syringes. This order was quickly brought to the Governor’s desk, signed, and implemented.

AMA urges states to adopt new Maine needle, syringe exchange policy

In Pennsylvania, SSPs have operated legally for more than 25 years in the state’s largest cities. But the state is one of only a few that have not modernized its drug paraphernalia code and declared SSPs legal at the state level. PA’s Governor recognized the critical role SSPs play in sustaining life, and despite the programs not being legal in the state, declared SSPs an essential service and their workers essential personnel.

Syringe exchanges deemed ‘life-sustaining’ during Pa. coronavirus shutdown, raising hopes for eventual legalization

In Illinois, public health workers have recognized the unique vulnerability faced by people who use drugs during COVID-19, particularly those who smoke stimulants and are likely to share stimulant smoking equipment. Funds have been allocated for the purchase of safer smoking kits, in order to prevent transmission of the coronavirus in this high risk group.

“During those few weeks, approximately one-quarter of SSPs in this sample reported closing at least one site. The rapid closure of many SSPs highlights the thin margins on which many of these programs operate. These closures could potentially have profound negative impacts on the health of PWID. The risk of fatal opioid overdose may increase due to decreased naloxone distribution. A reduction in sterile injection equipment available to PWID may increase risk for HIV, HCV, and other infectious consequences of injection drug use. Disruptions in the availability of HIV and HCV testing will further increase the likelihood of ongoing transmission in communities. Additionally, SSPs often provide direct or indirect linkage to treatment for substance use disorders, and the inability of PWID to access these services further increases their risk of morbidity and mortality.”

173 Syringe Service Programs Respond to COVID-19

In May 2020, a research study exploring the impact of COVID-19 on syringe service programs was published. This study included surveys of 173 SSPs and qualitative interviews with SSP staff from Detroit, Philadelphia, New Orleans, New York City, and Seattle.

- 43% of SSPs reported a decrease in availability of services due to COVID-19. (Decreased services: MAT, HIV/HCV testing.)

- One-quarter (25%) of responding SSPs reported that one or more of their sites had closed due to COVID-19.

SSPs also reported changing their service delivery model in response to COVID-19. Over one-half (53%) of SSPs are prepacking all supplies for participants, 20% are providing delivery services or only delivery services, and 6% are providing mail-based services. - Over one-quarter (27%) of SSPs reported that they are screening participants for COVID-19 symptoms.

- Programs have Adapted to Maximize the Safety of Their Staff and Participants:

- Programs have increased the amount of syringes and naloxone distributed at one time to reduce the overall number of visits to the SSP.

- Some programs pre-pack all supplies for clients.

- Many allow only 1 participant to enter the program at a time, while others have moved outside.

- Some programs are providing food for clients and others are providing suboxone via telehealth under the new regulations.

- Several programs have reduced staffing.

- PPE for staff is limited.

- Demand remains high for SSP services:

- Most SSPs reported that the number of participants seeking services has declined since social distancing measures were implemented

- Programs reported that the number of syringes distributed had remained level or had increased due to distributing more supplies to each participant, including through secondary exchange (i.e., providing supplies to peers to distribute to others).

- SSPs Remain Essential Services for PWID, But This is Not Always Recognized

- Some jurisdictions have explicitly designated SSPs as essential services.

- SSPs in other states have continued to operate through collaborations with other essential services.

- Nearly all SSP staff noted that policy makers and leadership had not included SSPs in jurisdictional emergency planning and response and were not able to provide informed guidance on the expectations for SSPs.

- Instead, program managers have been empowered to implement changes autonomously and involve SSP staff in these decisions.

- Several programs have utilized guidance on best practices in the COVID-19 era from large harm reduction organizations.

- Multiple organizations stated they hope this experience increases the visibility of the public health importance of SSPs.

- Syringe and Naloxone Distribution have been Prioritized, While HIV and HCV Testing have Declined

- SSPs can Provide COVID-19 Related Services to a Vulnerable Population

-

June 12, 2020

WEBINAR: Changing Barriers to MAT Accessibility in Iowa During COVID-19 | Friday, June 12 | 12:00 - 1:30 CDT

In 2019 an estimated 12,000 Iowans suffered from Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recognizes the combination of counseling and behavioral therapy with FDA-approved medications such as methadone and buprenorphine/Suboxone for treatment of OUD. In order to prescribe buprenorphine/Suboxone, the federal Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 mandates physicians complete 8 hours and advanced practice providers complete 24 hours of training to receive a waiver. Once they acquire this “X” waiver, providers can prescribe to a maximum of 30 patients in their first year, 100 patients in their second, and up to 275 patients thereafter. Iowa currently has 194 X-waivered providers in 35 of our 99 counties, and 8 methadone clinics in 5 counties. These regulations create enormous barriers to life-saving treatment for vulnerable Iowans. Now, with the expansion of telehealth due to COVID-19, a variety of state and federal restrictions to treating OUD have been lifted and Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) clinicians have had to adapt.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) announced on March 16th that due to the COVID-19 pandemic it will exempt Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) Clinics from requiring monthly (for buprenorphine) or daily (for methadone) in-person physical exams on patients before prescribing them medications for Opioid Use Disorder. This allows providers to treat their patients with life-saving medication without requiring them to travel for regular check-up visits and risk viral exposure. SAMHSA has said these exemptions may cease after the pandemic, but these changes give MAT supporters a unique opportunity to advocate for continued deregulation and reduction in barriers to care. This webinar will feature public health experts, state and federal government officials, Iowans affected by Opioid Use Disorder, and MAT clinicians from multiple Iowa communities. Speakers will discuss the changing barriers to MAT access during the COVID-19 pandemic and highlight areas where further action is needed. This webinar will be recorded and a written summary with key recommendations for next steps will be disseminated.

Our hope is to provide a space for healthcare professionals, policy makers, and those affected by OUD to have a discussion about how we can capitalize on this rapid restructuring of MAT services. The goal of this webinar is to identify a set of recommendations that individual speakers would like to make for stakeholder groups at federal, state and local levels.

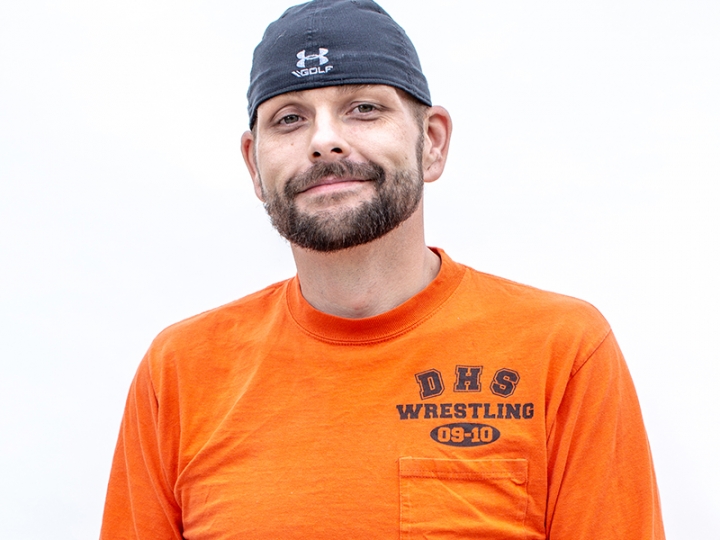

Chad Fairchild,

MAT patient

Kyle Wiand,

IHRC volunteer

Dr. Alison Lynch,

Director of Addiction Medicine, Psychiatrist and MAT Provider, University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics

Jen Pearson,

CEO, UCS Healthcare

Monica Wilke-Brown,

Opioid State Targeted Response Grant Director, Iowa Department of Public Health

Evelyn Fortier,

Health Policy General Counsel, Office of Senator Charles Grassley

Anna Bonelli,

Senior Policy Advisor, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (HHS)

Shannon Lundgren,

Representative (R-Dubuque), Iowa Legislature